Clothes can be forms of thought as articulate as a poem or equation. Why then does philosophy like to dress them down?

Sometime in 1932, Salvador Dalí met with the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. A deliciously queer photograph records them loitering together in a Parisian street, swaddled in fur coats so sumptuous that Liberace would have died of envy. Dalí’s is draped insouciantly across his shoulders like a black cape, his straggly collar-length hair lending him a vampiric air. But Lacan, distracted, has his hands shoved in his pockets, and the coat, a plush and stripy affair, mink perhaps, is a kind of nonchalant afterthought.

That Lacan should be a dandy is predictable enough to those familiar with his writings on the ‘mirror stage’ of infant development. For Lacan, no account of the ego is complete without narcissism, the gaze and the ‘specular image’ – the idea that selfhood is profoundly bound up with the ways in which we are seen from the outside. Lecturing to a captivated audience at the University of Leuven in 1972, grainy film footage records him as imperious, idiosyncratic and, it turns out, fond of pussy-bowed paisley-print chemises. Puffing at a fat cigar, his hands strain and curl with the intensity of his efforts at articulation: ‘Language,’ he says, ‘never gives, never allows us to formulate…’

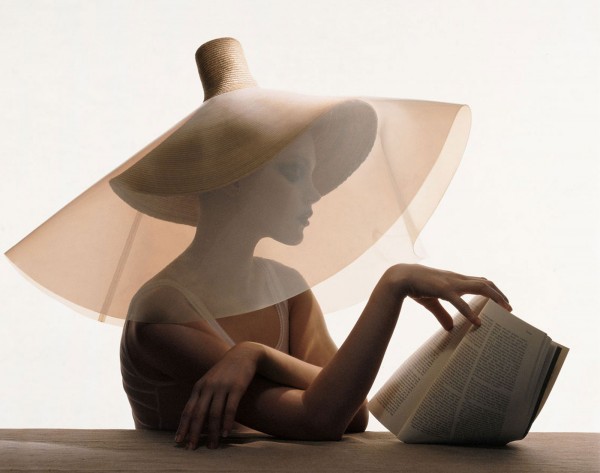

Where language falls short though, clothes might speak. Ideas, we languidly suppose, are to be found in books and poems, visualised in buildings and paintings, exposited in philosophical propositions and mathematical deductions. They are taught in classrooms; expressed in language, number and diagram. Much trickier to accept is that clothes might also be understood as forms of thought, reflections and meditations as articulate as any poem or equation. What if the world could open up to us with the tug of a thread, its mysteries disentangling like a frayed hemline? What if clothes were not simply reflective of personality, indicative of our banal preferences for grey over green, but more deeply imprinted with the ways that human beings have lived: a material record of our experiences and an expression of our ambition? What if we could understand the world in the perfect geometry of a notched lapel, the orderly measures of a pleated skirt, the stilled, skin-warmed perfection of a circlet of pearls?

Some people love clothes: they collect them, care for and clamour over them, taking pains to present themselves correctly and considering their purchases with great seriousness. For some, the making and wearing of clothes is an art form, indicative of their taste and discernment: clothes signal their distinction. For others, clothes fulfill a function, or provide a uniform, barely warranting a thought beyond the requisite specifications of decency, the regulation of temperature and the unremarkable meeting of social mores. But clothes are freighted with memory and meaning: the ties, if you like, that bind. In clothes, we are connected to other people and other places in complicated, powerful and unyielding ways, expressed in an idiom that is found everywhere, if only we care to read it.

Get the complete essay on AEON